All in One: The Individual and the Group in Jonathan Gold’s Oeuvre

Neta Gal Azmon

The individual seeking his place and identity in the world, while conducting an ambivalent dialogue with the group to which he belongs, is a central theme in Jonathan Gold’s (b. 1972, Kibbutz Afek) works. Even when he paints a landscape or still life, Gold focuses almost exclusively on the human figure. Like a researcher facing a detective mystery, an anthropologist examining a remote tribe, or a participant observer studying his own reference group, Gold traces the point of departure, the ground into which he was born and on which he was raised, which outlined and established his adult identity. He usually places his protagonists in domestic environments (at home, in office spaces, or in public showers). In other instances, the background to the occurrence remains abstract, implied as an urban space or characterized as a wild landscape, set against a social gathering. Either way, it is the human story that is given center stage in his work. The relationship between the human body and its immediate, mundane physical environment, and the complex interactions between the individual and the group to which he belongs, or would have liked to belong, are addressed in his paintings over and over again, woven together. They articulate an internal narrative, underlain, according to Gold, by a comprehensive ideological view, which he defines as “local secularism.” His identity as an artist, he attests, was formed over the years out of keen awareness of his definition of himself as a secular Israeli artist, and more specifically—as a kibbutz-born secular Israeli painter.

I was born and raised on a kibbutz in northern Israel. Life in a communal society has had a great impact on my art, understanding that everything must exist in relation to or in connection with the society around me. It is no coincidence that most of my paintings depict relationships within a group, or an attempt by the individual to find his place within modern systems.[1]

In this context, it is interesting to examine Gold’s lively dialogue with New Horizons, a group of painters active in Israel between 1948 and 1963, from whose members he draws great stylistic inspiration, he says. His works indeed echo not only the group members’ strong tendency to emphasize the pictorial means, but also their fascination with the abstract. In contrast to the New Horizons artists, however, whose abstraction related to the local landscape, Gold seems to direct an implicit spotlight at Israeli culture, which he interprets, as aforesaid, in terms of power and the toll of belonging to the group. As opposed to the focus on a neutral, morally indifferent nature, Gold charges his brush with conflictual questions stemming from the engagement with human beings and the hierarchies of power they establish and nourish. In addition to the stylistic influence of New Horizons on Gold’s work, it seems that the heated conflict between the New Horizons artists and the members of the Israel Painters and Sculptors Association[2]—the canonical mainstream of those years in Israel—is ingrained in Gold’s work, evident in his treatment of the tension between the individual and the group, and the relationships among group members. In this context, it should be noted that the founders of New Horizons resigned from the Painters and Sculptors Association due to intense artistic and other disagreements. They “wanted to promote the influence of international art on visual art in Israel… were intrigued by European modernism, hence also advocated ‘art for art’s sake’, as well as the need to express the individual’s uniqueness, rather than the power and mission of the group.”[3] This tension between the individual and the group was one of the pretexts for the schism, and the embarkment of the New Horizons artists on their separate path.

Gold depicts groups at work (much like Yohanan Simon, for instance, who painted family scenes set against the kibbutz habitat), but he does not portray the group or its members in an admiring light: his “story” delves into a multi-participant gathering described as banal, unglamorous, at times tense. The perspective on communal life, whether professional or social, thus acquires a critical or, at least, an ambivalent dimension. In contrast to Simon’s monumental figures, which radiate health, power, optimism, and harmony with nature, Gold’s figures are schematic and flat. One can imagine Gold observing the events from a distance of time and place, already beyond the “age of innocence,” equipped with the sober, painful knowledge about the grim fate of the glorious kibbutz enterprise, where he was raised and educated. Nevertheless, it seems that the group, and the deep memories it has imprinted in him, for better or worse, is etched deep in his heart, activating him and making his soul rage, to this day. “However far they roam, the original ‘natal group’ will always follow, like a mirror-image reflected in the sky and branded into its members’ minds.”[4]

The figures in Gold’s paintings usually gather for the purpose of realizing a specific task. In this regard, he attests to the impact of the collective Israeli experience, which plays a dominant role, he believes, also in this action and work context. His paintings do not convey a sublime experience associated with the solitary individual in the landscape (as in Caspar David Friedrich’s renowned painting The Monk by the Sea, 1808–10, for example), since the individual in his paintings usually appears as part of a group, as Gold puts it humorously: “Here one doesn’t stand by himself in a lake; we have the crowded Sea of Galilee.”

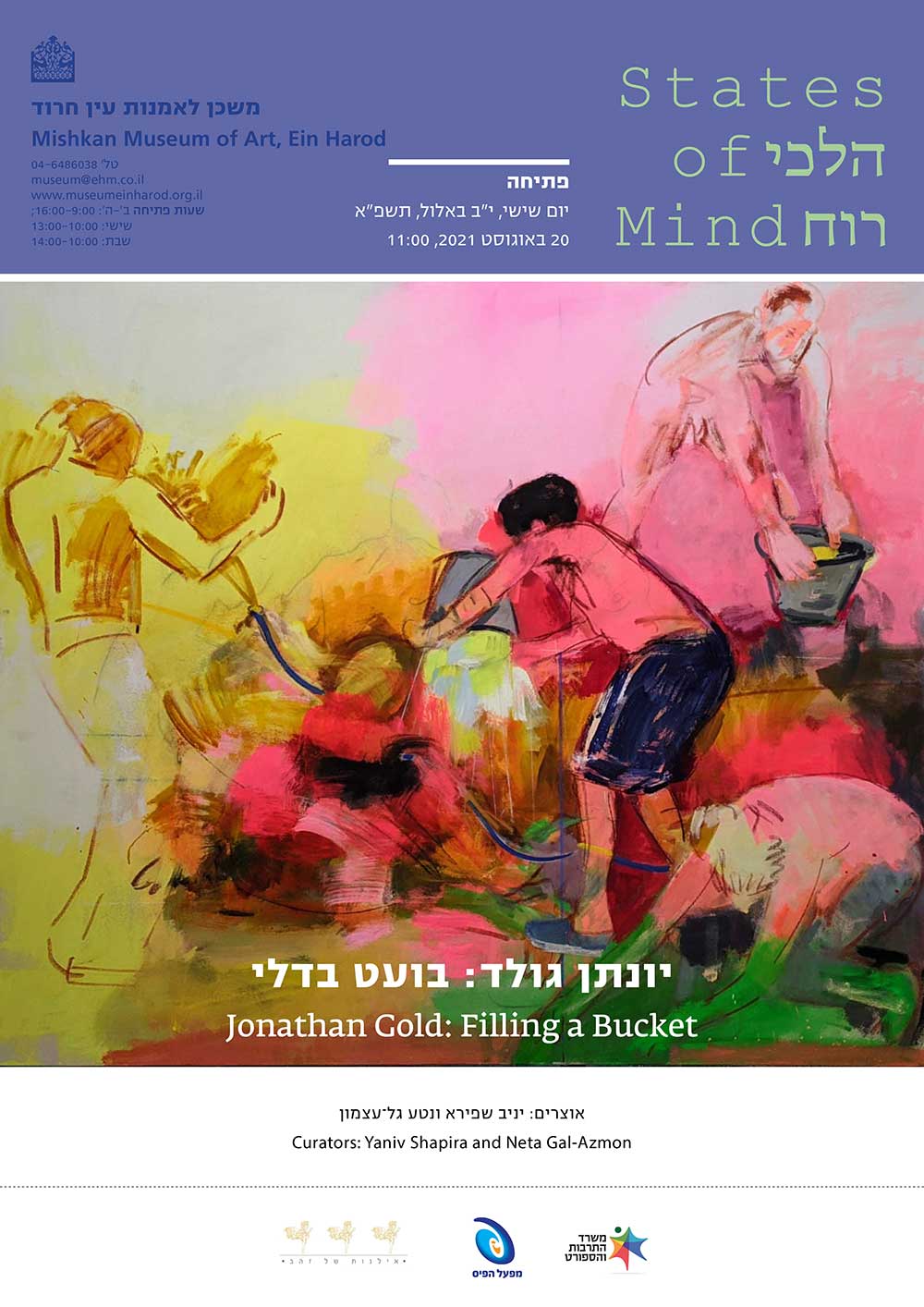

Gold’s brush seeks the “right distance” for a reflexive engagement with these complex issues that have shaped his personality. The art of painting, by its very nature, makes for an intense, intimate exploration of charged themes from a sufficient distance, allowing for the same margin of safety at the service of the reflexive gaze. His painting style ranges from the figurative to the abstract. Thus, although one may attribute narrative characteristics to his paintings (one may formulate some insights about the nature of the activity before us, as well as the setting in which it takes place), the human figures and their environment are depicted with broad, flat brushstrokes, almost schematically. Gold does not dwell on a detailed depiction of facial features and body parts, and unlike other painters, he draws away from realism.

One may regard his decision to blur concrete characteristics of his protagonists and portray them in generic terms in the context of the kibbutz habitat, which aspired to equality and blurring differences, and emphasized practical purposefulness. In this approach, Gold’s painterly style may be regarded as another means of illustrating the mindset represented in the works. The narrative space is identifiable, and at the same time it is unraveled and open to interpretation and active reading of the work. Despite the figures’ flatness, Gold’s paintings radiate a strong, energetic physical presence, arising from the large-scale portraits as well as the paintings of inanimate objects, whether the houses or the buckets, which ostensibly complement them. These fill the bulk of the canvas with intense, sensual coloration. Gold’s bodies (human and inanimate alike) constitute a narrative and compositional center of gravity, from which the entire painting unfolds. The emphasized corporeality, further reinforced by the particular coloration, which is obtained by using self-prepared paints (as opposed to the glossy effect resulting from the use of ready-made industrial oil paints), reinforces this feeling. Similarly, the painterly work likewise presents itself as an action/labor. It begins with grinding and manually mixing pigments with different types of adhesives until the desired hue and quality are obtained; it continues with stretching canvases on large wooden frames, and its core is the act of painting, which is performed with large, wide brushstrokes. In this context, one should add, that in Gold’s paintings there is no localized occurrence or vanishing point, nor is the gaze guided within the composition. The painting seems to emerge “all at once.”

The nudity, conspicuous in Gold’s paintings, may be construed as an attempt to delve deeper, to see past his protagonists’ outer envelope. The naked figures do not convey serenity and integration with nature; on the contrary—they evoke restlessness. In addition to the somewhat brutal eroticism they display (echoing Jewish collective memory which connects communal showers and annihilation), they mainly emphasize power relations, hierarchy, and the exercise of power through social structure. In some instances, the nudity seems narratively required and ostensibly justified by the situation (as in the paintings of bathers/dressers), while in others it is puzzling and enigmatic. In these cases (as in the series of admissions committee paintings) it appears like a Dionysian provocation, defying the decency of public order. Either way, its pronounced presence in the two major series mentioned above suggests a thematic connection between them, despite their apparent divergence. Each series, in its own way, addresses a dialectic underlying a profound human experience along the continuum between the aspiration for authenticity and individualism and the desire to belong to a collective, to be part of a group. In both series, the individual confronts the group (or appears as part of it) in a situation that calls for judgment and criticism. The exposed, sweeping nudity, appearing in its ostensibly “natural” context in the bathing paintings, emerges as an expression of the primal, beastly, primordial, that which, according to Gilles Deleuze’s terminology, brings us positively closer to the animal spirit.[5]

The admission committee paintings, on the other hand, offer a reference to identity in its artificial sense, as an artifact, as a false self. As such, it calls for presentation of the representative, beautified, seemingly civilized aspects of the self. In these situations, the depiction of the self reflects a human need to belong to a coveted group, to gain validity and recognition.

The dominance of the nudity motif in both series indicates their common denominator, as well as the fact that each of them exposes the latent apparatuses invisible to the other. In the concrete or metaphorical group nudity scenes, which are a routine part of the Israeli experience, the “admissions committee,” in all its cruelty, plays a part from a very young age. Exposure of the body in the concrete group context may be associated with school trips, youth movement hikes, and the military service. The less concrete complexity of socialization processes, radicalized in these paintings, begins early in life and occurs in every human setting. The bestial, instinctive, and primal bursts into the seemingly “decent,” “cultural” situation of the actual and symbolic admission committees in our lives as a mirror image. Either way, the nudity in Gold’s paintings evokes associations pertaining to boundaries and demarcation and their absence. On the one hand, it is presented in the context of “the committee” as a concept that indicates an undisputed authority, in whose name and through that authority (be it as it may) social dictates are decreed, which give rise to an uncompromising, at times intrusive, violent reality. On the other hand, within the group itself, the nudity reveals the blurred boundaries and often their collapse. It seems that every intense human gathering produces a reality in which everyone is exposed to everyone. In such a state of affairs, the metaphorical nudity, like the concrete one, is not a nudity of voluntary devotion, but rather a forced nudity, and sometimes perversion raises its head out of the perplexity. That the figures are depicted almost without a background or in an abstract setting, without an organizing structure, reinforces the absence of a protective experience of a home, in its desired function as an envelope sheltering the individual from the other, from the group.

[1] Gold in a conversation with the undersigned ahead of the exhibition.

[2] The Israel Artists and Sculptors Association (as it is called on the Membership Card) originated in the Jewish Artists Association established in October 1920. Beginning in 1923, it staged numerous group exhibitions, eclectic in their quality and artistic level. The painting style of its members may be characterized as a figurative Eretz-Israeli style.

[3] Yigal Zalmona, A Century of Israeli Art (Surrey, UK and Jerusalem: Lund Humphries and the Israel Museum, 2013), p. 163 [Hebrew].

[4] Tali Tamir, “Constellations: On Nearness and Distance,” cat. Togetherness: The ‘Group’ and the Kibbutz in Collective Israeli Consciousness, trans. Ishai Mishory (Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 2005), p. 214.

[5] Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2018 [1987]), p. 170.